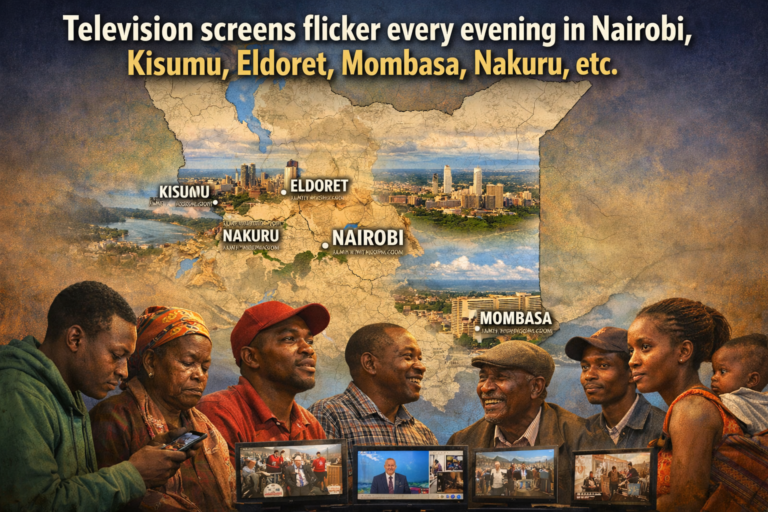

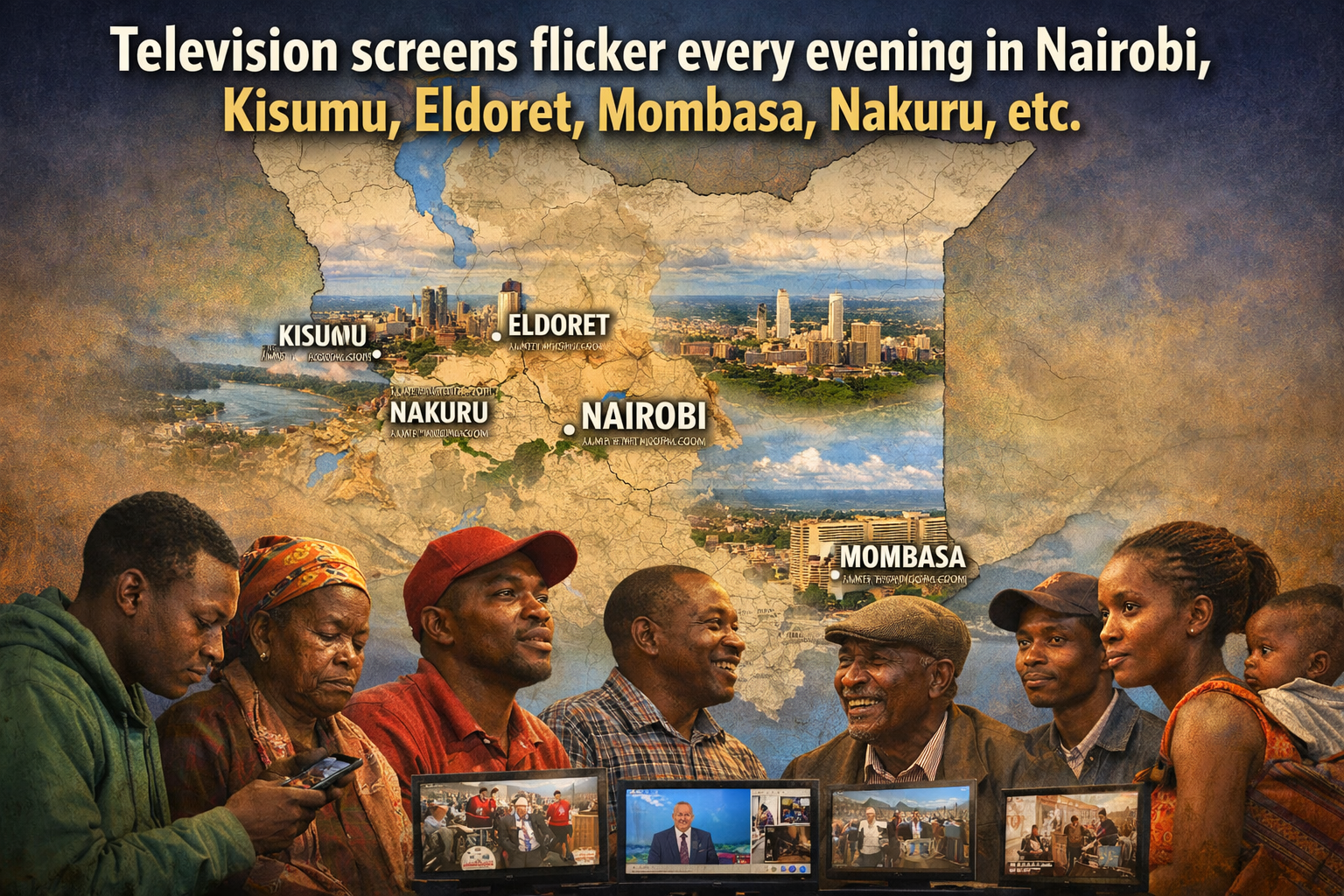

Television screens flicker every evening in Nairobi, Kisumu, Eldoret, Mombasa. The anchors speak with calm authority. Panels debate strategy, alliances, personalities. Headlines scroll across the bottom of the screen. Yet a growing number of viewers no longer experience these broadcasts as neutral reporting. They see choreography. They see scripts polished long before cameras turn on. They see narratives that protect powerful networks rather than interrogate them.

Kenya’s mainstream media once carried the aura of defiance. In the 1990s and early 2000s, journalists confronted state excesses, exposed scandals, and risked retaliation. That era shaped public trust. Newsrooms were viewed as imperfect but courageous. Over time, ownership structures shifted. Media houses expanded into corporate conglomerates. Advertising revenue tightened. Government became one of the largest advertisers. Editorial independence began to intersect with commercial survival.

When survival depends on advertising contracts, caution creeps in. Critical stories are weighed against potential backlash. A hard investigation into procurement deals may threaten access to government campaigns. A probing documentary might jeopardize regulatory approvals. Editors deny pressure; reporters speak quietly about calls from powerful offices. The audience rarely hears those calls. What it hears are softened headlines and carefully balanced panels that rarely move beyond the safe perimeter of acceptable criticism.

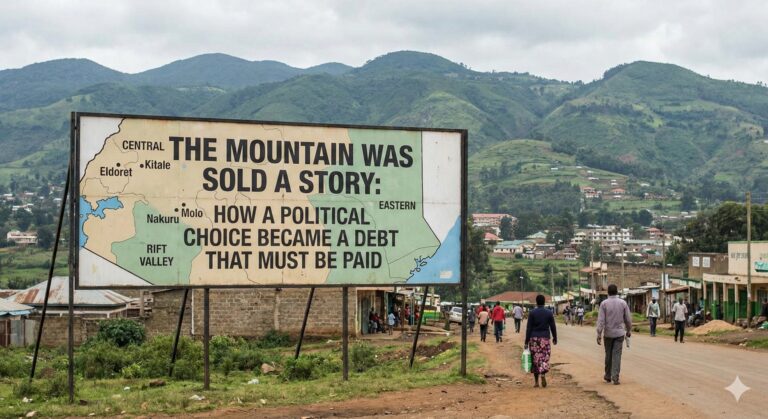

The approach becomes visible during election cycles. Political branding floods airwaves. The 2022 campaign elevated the “wheelbarrow” into a national emblem of empowerment. Coverage amplified the symbolism. Studio discussions revolved around its meaning, its appeal, its resonance with hustler narratives. Questions about economic feasibility often received less sustained attention than the imagery itself. The object became spectacle. The policy details remained peripheral.

Now, as 2027 approaches, a new sequence unfolds. “Singapore” enters conversation as shorthand for ambition and development. “Sikiza ground” circulates as proof of proximity to ordinary citizens. Rival ODM factions dominate headlines. Kalonzo Musyoka and the Wiper movement reappear in alignment talks. Martha Karua mobilizes her own camp. Justin Muturi signals recalibration. Each realignment commands prime time. Each meeting receives live coverage. Viewers absorb a steady stream of political theater framed as ideological contest.

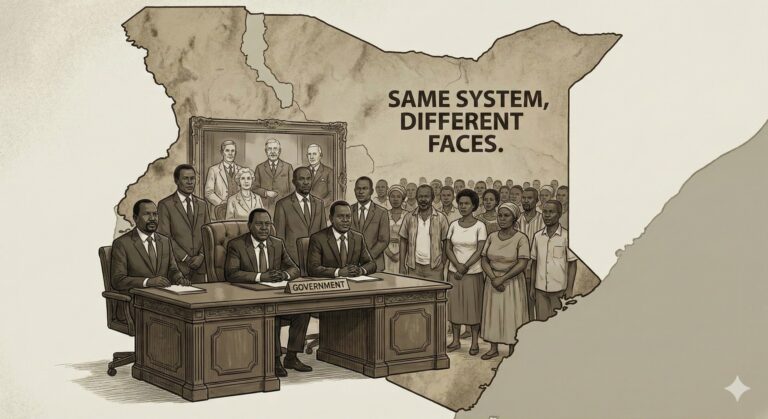

Yet beneath that surface, many citizens sense repetition. Parties fracture, merge, rename, reposition. Leaders denounce one another in the morning and negotiate in the evening. Media narrates each shift as dramatic rupture. The deeper pattern appears constant: bargaining for leverage ahead of power distribution. Cabinet slots. Committee chairs. Procurement access. Coalition arithmetic. The public watches the dance without seeing the contract being drafted behind closed doors.

This perception feeds the argument that mainstream outlets function less as watchdogs and more as amplifiers. Investigations into land scandals, debt obligations, or security procurement often stall at partial disclosure. Panelists debate personalities instead of structural incentives. Opinion columns oscillate around strategy rather than accountability. A scandal erupts; a press conference follows; a denial circulates; the story fades.

Ownership matters. Several leading Kenyan media houses belong to individuals with business interests extending beyond journalism. Investments span banking, real estate, manufacturing, energy. Regulatory decisions affecting those sectors originate within the same political arena being covered. The conflict need not be explicit. Self-restraint becomes internalized. Editors anticipate risk. Reporters learn which stories stall careers.

Digital platforms complicate the terrain. Social media injects raw footage and citizen commentary into public discourse. Yet mainstream outlets retain gatekeeping power. They select which clips to validate, which narratives to elevate. A protest video may trend online for hours before a television station addresses it. When it does, framing shapes interpretation. Language calibrates emotion. Emphasis signals priority.

Many citizens consume news habitually. Morning radio in matatus. Evening bulletins at home. Weekend political talk shows. The routine feels civic. Few pause to interrogate the economic structure behind each broadcast. Who funds this program? Which corporations advertise here? Which regulatory body oversees the station? Which political networks intersect with ownership?

The stakes rise as elections approach. Campaign spending surges. Advertising slots become coveted assets. Political rallies receive live feeds. Slogans circulate without sustained scrutiny. Coverage often mirrors campaign strategy. A candidate tours counties; cameras follow. A coalition fractures; anchors speculate. Rarely do viewers receive sustained analysis of fiscal plans, debt restructuring proposals, land reform blueprints, or institutional redesign.

The frustration extends beyond media performance. It touches the character of Kenya’s democracy. Independence arrived in 1963 under a state built for extraction. Colonial administration centralized authority, controlled land, and prioritized revenue flows outward. That architecture did not disappear at Uhuru. Control transferred. The machinery remained. Centralized executive power persisted. Resource allocation followed political loyalty. Patronage replaced foreign oversight.

For six decades, elections have offered periodic change in leadership. They have not consistently altered the distribution of economic opportunity. Youth unemployment persists. Informal labor dominates. Public debt expands. Living costs strain households. Elite networks accumulate wealth through state contracts, land speculation, and financial leverage. Many citizens interpret this continuity as structural, not accidental.

Media could interrogate that continuity. It could trace procurement networks across administrations. It could map campaign financing to post-election appointments. It could analyze budget allocations with sustained rigor. Instead, coverage often gravitates toward personality drama. Rivalries between figures overshadow structural examination. Viewers become spectators of elite competition rather than participants in policy discourse.

This pattern influences civic expectations. Elections resemble tournaments between networks rather than contests between governing philosophies. Political branding dominates. The wheelbarrow symbolized grassroots ascent. “Singapore” suggests rapid modernization. “Sikiza ground” implies humility. Each slogan captures imagination. Few broadcasts dissect feasibility, institutional capacity, or fiscal constraints with sustained depth.

Critics argue that democracy requires institutions insulated from elite bargaining. An independent judiciary. A professional civil service. Transparent procurement systems. A media sector free from financial capture. Kenya’s constitution of 2010 attempted institutional recalibration. Devolution redistributed authority to counties. Independent commissions emerged. Gains are real; limitations persist. Central influence remains potent. Budget control shapes compliance.

The feeling of exclusion intensifies when economic pressure mounts. Fuel prices climb. Food inflation erodes wages. University graduates search for work. Small enterprises struggle with taxation and regulatory costs. Citizens tune into news seeking clarity. They receive campaign rallies and alliance updates. Structural debate recedes.

Some journalists resist. Investigative teams publish exposés on procurement irregularities, land grabbing, security abuses. These stories surface intermittently. They spark outrage. Follow-through weakens. Legal processes stall. Political momentum shifts. The cycle resets. Public memory fragments.

Digital-native outlets and independent reporters fill gaps. Crowdfunded investigations bypass traditional advertisers. Podcasts dissect fiscal policy with candor. Online platforms host long-form analysis absent from prime time television. Yet reach varies. Mainstream channels still command the largest audiences. Their editorial direction shapes national conversation.

As 2027 approaches, rhetoric intensifies. Campaign caravans tour counties. Opinion polls proliferate. Alliances recalibrate weekly. Media houses scramble for exclusives. The spectacle grows. Structural questions linger. Can electoral competition dismantle patronage networks rooted in colonial administration? Can media houses reliant on political advertising interrogate those who finance them? Can citizens demand fiscal transparency beyond campaign season?

Public trust fluctuates. Surveys reveal declining confidence in institutions, including media. Listeners question headlines. Viewers scrutinize panel composition. Social media threads dissect broadcast framing. Skepticism expands. Cynicism shadows engagement.

Still, democratic space exists. Courts have occasionally constrained executive overreach. Civil society litigates. Youth movements organize. Whistleblowers surface documents. Media sometimes amplifies these efforts. The relationship between press and power remains contested rather than fully captured.

Kenya’s future hinges less on replacing one alliance with another and more on reconfiguring incentives embedded in governance. If procurement transparency becomes automatic, patronage shrinks. If campaign financing disclosures become mandatory and enforceable, bargaining shifts. If media ownership diversifies and revenue models reduce dependence on state advertising, editorial autonomy strengthens.

The frustration expressed by many citizens reflects fatigue with repetition. Campaign symbols rotate. Personalities realign. Economic hardship persists. News broadcasts chronicle movement without tracing root causes. Elections promise renewal; structures endure.

Accountability requires sustained attention, not episodic outrage. It requires data, memory, and institutional insulation. Journalism, at its best, archives evidence and tracks patterns across administrations. When it drifts toward packaging elite messaging, democratic oversight weakens.

Kenya stands at another electoral threshold. Television studios glow. Radio debates intensify. Social media pulses with slogans. Beneath that noise lies a simpler demand voiced in markets, campuses, and estates: governance that distributes opportunity beyond elite circles. Media could elevate that demand with persistent scrutiny. Whether it will depends on ownership, revenue, professional courage, and public insistence.

Citizens continue to watch. Some watch skeptically. Some switch platforms. Some disengage. The cycle moves toward 2027. Alliances shift again. The deeper contest concerns not only who wins office, but whether institutions can be insulated from capture and directed toward broad-based prosperity rather than narrow accumulation.

That outcome will not be determined solely at rallies or in studios. It will hinge on whether structures built for extraction can be redesigned for inclusion, and whether those tasked with informing the nation choose to interrogate power rather than echo it.