The Convenient Lies We Built a Nation On

December 12, 1963. Flags waved across Kenya as Jomo Kenyatta stood before thousands, declaring uhuru—freedom. The British handed over power with carefully choreographed pageantry. Cameras captured smiling faces, dignified handshakes, the promise of a bright future. What those cameras didn’t capture was the blood still fresh in detention camps, the screams of tortured freedom fighters echoing in pipeline prisons, or the quiet betrayals already being planned by men in expensive suits. Kenya’s independence wasn’t won through diplomatic negotiations in Lancaster House. It was seized by men and women who fought with guns, pangas, and their bare hands in forests and mountains. Yet the official story we learned in schools sanitized this violence, elevated certain figures to heroic status, and conveniently erased others who proved too radical, too honest, or too dangerous to the new political order.

The monuments we built tell a particular story. Statues of founding fathers gaze benevolently over city squares. Streets bear names of liberation heroes. Museums display artifacts of the struggle. But scratch beneath the bronze and marble, and a different history emerges—one of convenient omissions, strategic mythmaking, and historical airbrushing. The men who truly terrified the colonial administration, who refused to compromise their principles, who died with dirt under their fingernails and bullets in their chests—these men were systematically written out of our national narrative or reduced to footnotes. Their crime? They represented a vision of Kenya that threatened the interests of those who ultimately claimed the spoils of independence.

This erasure wasn’t accidental. It was deliberate, calculated, and essential to maintaining power in the post-colonial state. The new African elite needed legitimacy, and legitimacy required heroes who could be controlled, mythologized, and safely dead. Living revolutionaries with memories of broken promises and unfulfilled dreams posed too many questions. So Kenya’s official history became a carefully curated gallery of acceptable heroes, their rough edges smoothed, their radical politics sanitized, their inconvenient truths buried under layers of propaganda. Sixty years later, we’re still living with the consequences of these foundational lies.

The Kapenguria Six: When Brothers Became Prisoners

October 1952. British colonial authorities arrested six men and charged them with managing Mau Mau, an oath-taking society dedicated to violent overthrow of colonial rule. The trial location—Kapenguria, a remote outpost near the Uganda border—was chosen specifically to prevent public demonstrations. Jomo Kenyatta, Bildad Kaggia, Kung’u Karumba, Fred Kubai, Paul Ngei, and Achieng Oneko stood accused. The evidence was flimsy, witnesses were coached, and the verdict was predetermined. The British needed scapegoats, symbols they could imprison to demonstrate control over a rebellion spreading like wildfire across the central highlands.

These six men shared cells, shared suffering, and shared dreams of what independent Kenya might become. They spent years together in detention—first at Lokitaung in the northern desert, then at Lodwar. They discussed land redistribution, economic justice, education for the masses. Kaggia, a former soldier who had traveled to England and returned radicalized, spoke passionately about socialism. Oneko, a journalist, documented their experiences. Karumba and Kubai, trade union organizers, understood working-class struggles. Kenyatta, the eldest and most internationally known, served as their leader. They believed they were fighting for a Kenya where the poor would inherit the land stolen by settlers, where resources would be shared, where the color of your skin or your family connections wouldn’t determine your opportunities.

Prison changes men. Sometimes it hardens their convictions. Sometimes it breaks their spirits. Sometimes it reveals who they truly are. The Kapenguria Six entered detention as comrades. They emerged as something else entirely. Kenyatta spent those years not just enduring hardship, but planning. He watched his fellow prisoners maintain their radical commitments. He nodded along with their discussions of socialist transformation. But behind his eyes, calculations were being made. The British were losing their grip on Kenya. Independence was coming. Someone would need to lead the new nation. Someone the British could tolerate. Someone who understood that true power required compromises that idealists like Kaggia would never accept.

Dedan Kimathi: The Forest Fighter They Couldn’t Tame

The Forest Became Home

Kimathi and thousands of fighters lived in mountain caves, surviving on stolen livestock and foraged food, building a parallel government in the wilderness.

Oath-Taking Ceremonies

Binding rituals created unbreakable bonds between fighters, ceremonies the British labeled as savage barbarism but which represented serious political commitment.

The Pipeline System

British concentration camps held over 150,000 Kikuyu civilians, using systematic torture to break support for forest fighters and terrorize entire communities.

Dedan Kimathi Waciuri refused every compromise. Born in 1920 in Nyeri, he worked as a farm laborer on European estates, experiencing firsthand the casual cruelty of settler colonialism. He watched white farmers prosper on stolen land. He saw Africans reduced to squatters on their ancestral soil. He understood that polite petitions and constitutional negotiations would never dislodge an empire built on violence. So he took up arms. By 1953, Kimathi had become the most wanted man in Kenya, with a £1,000 bounty on his head—more than the annual salary of most Africans. He commanded Mau Mau forces in the Aberdare forests, coordinating attacks, maintaining discipline, articulating a vision of total liberation.

The colonial government portrayed Kimathi as a terrorist, a savage, a murderer. Newspapers ran lurid stories about Mau Mau atrocities. The violence was real—civilians died on both sides, some in horrific ways. But British propaganda carefully omitted context. They didn’t mention the Land and Freedom Army (Mau Mau’s self-chosen name) formed in response to decades of land theft, forced labor, pass laws, and systematic oppression. They didn’t report on concentration camps where British forces tortured and killed thousands of Kikuyu civilians. They didn’t acknowledge that Kimathi’s fighters were responding to structural violence that had destroyed their communities. The official narrative required monsters, not freedom fighters driven to desperate measures by intolerable conditions.

October 21, 1956. British forces captured Kimathi in the Nyeri forest. He’d been betrayed by an informant, shot in the leg, and taken alive. The trial lasted weeks, the verdict never in doubt. They hanged him on February 18, 1957, at Kamiti Prison. His body was buried in an unmarked grave, location unknown to this day. The colonial government wanted no shrine, no pilgrimage site, no martyr’s tomb. Kimathi had to disappear completely. After independence, the Kenyatta government maintained this erasure. Kimathi represented an uncomfortable truth—that armed struggle, not negotiation, had truly threatened British rule. Kenyatta, who had spent the emergency years in detention, emerged to claim credit for a victory won by fighters like Kimathi who had actually bled for it. Acknowledging Kimathi’s contribution would raise questions about who deserved power in independent Kenya.

The Betrayal: When Kenyatta Chose Power Over Principles

Uhuru arrived with promises. Kenyatta spoke of African socialism, of land redistribution, of opportunities for the masses who had suffered under colonialism. His former prison mates believed him. Bildad Kaggia returned to his Kandara constituency, organizing landless squatters, demanding the government fulfill promises made during the struggle. The land hadn’t been liberated for African elites to simply replace white settlers. It belonged to the people who had fought and died for it. Kaggia reminded Kenyatta of their prison discussions, their shared dreams of economic justice. He expected his old comrade to champion radical redistribution.

What happened instead remains one of Kenya’s defining betrayals. Kenyatta surrounded himself with former colonial administrators, conservative businessmen, and Kikuyu elite who had never joined the forest fighters. Land reform became a mechanism for enriching the already wealthy. Settlers sold their farms at inflated prices to African buyers with government loans. The landless remained landless. Squatters who had sheltered Mau Mau fighters found themselves evicted by African landlords. When Kaggia protested these injustices, Kenyatta turned on him viciously. At a 1965 rally in Kandara, the president asked what Kaggia had done for himself during the independence struggle. “We were together in prison,” Kenyatta sneered. “What have you done for yourself? If you go on opposing, we will crush you into flour.”

The message was clear. The independence struggle had been about power, not justice. Those who had actually fought—the landless peasants, the squatters, the former forest fighters—were expected to accept whatever scraps the new elite chose to throw them. Kaggia and his fellow radicals from the Kapenguria Six found themselves marginalized, their political careers destroyed. Achieng Oneko was detained without trial in 1969. Kung’u Karumba disappeared into obscurity. Fred Kubai was harassed and impoverished. Paul Ngei survived by abandoning his principles and joining Kenyatta’s patronage machine. The brotherhood forged in prison shattered because one man chose personal power over collective liberation. Kenyatta’s betrayal established a template that has defined Kenyan politics ever since—liberation rhetoric masking elite accumulation.

JM Kariuki: The Millionaire Who Spoke for the Poor

1929

Born in Rift Valley, becomes Mau Mau fighter in his youth

1953-1960

Detained without trial, spends seven years in colonial detention camps

1963-1974

Elected MP, becomes wealthy businessman but champions the poor and landless

1975

Murdered, body dumped in Ngong Hills, state-sponsored assassination suspected

Josiah Mwangi Kariuki was a contradiction. He made millions in post-independence Kenya through business deals and political connections. He lived comfortably, drove expensive cars, wore tailored suits. Yet he used his parliamentary platform to denounce the growing inequality suffocating Kenya. His 1974 speech remains one of the most quoted critiques of Kenyan politics: “We do not want a Kenya of ten millionaires and ten million beggars.” Simple words. Devastating truth. JM, as everyone called him, had credibility because he’d suffered in detention camps, because he’d fought for independence, because he understood viscerally what the struggle was supposed to achieve. His wealth made him dangerous—he couldn’t be dismissed as a bitter failure motivated by envy.

JM’s speeches grew increasingly confrontational. He named names. He exposed land-grabbing schemes. He detailed how political elites were using their positions to accumulate property, businesses, and wealth while unemployment soared and squatters lived in squalor. The Kenyatta government, now thoroughly corrupt and authoritarian, watched him nervously. Some politicians urged him to moderate his tone, to work within the system, to understand that change required patience. JM refused. He’d spent seven years in detention camps dreaming of the Kenya they were building. That dream was dying, strangled by greed and tribalism. Someone needed to speak truth, consequences be damned.

March 2, 1975. JM disappeared after leaving the Hilton Hotel in Nairobi. His family reported him missing. Police claimed they were investigating. Days passed. Then a gruesome discovery—his body, badly decomposed and partially eaten by hyenas, found in the Ngong Hills. The official story claimed robbery. Nobody believed it. The murder was professional, calculated. JM’s last speeches had attacked powerful figures by name. His death sent a clear message: shut up or die. Thousands attended his funeral, many weeping openly. Students rioted at the University of Nairobi. The government banned all public gatherings. No serious investigation followed. The killers were never found because everyone knew who ordered the hit. Kenya had murdered one of its bravest sons for the crime of demanding the country live up to its founding promises.

Pio Gama Pinto: The Revolutionary They Erased

Pio Gama Pinto doesn’t appear in most Kenyan history textbooks. His statue doesn’t grace any major roundabout. No government building bears his name. This erasure is deliberate. Pinto was everything the post-independence elite feared—a committed socialist, a brilliant organizer, and someone whose dedication to justice never wavered. Born in Kenya in 1927 to Goan parents, Pinto could have claimed distance from the African struggle. He could have maintained the in-between status that Asians occupied in colonial Kenya’s racial hierarchy. He refused. Pinto joined the Kenya African Union, worked closely with independence leaders, and when the emergency was declared, he was detained for his activities supporting the liberation movement.

After independence, Pinto continued fighting for the radical transformation that others had abandoned. He founded the Pan African Press, published Mwafrika newspaper, and used these platforms to advocate for socialist policies. He worked closely with Bildad Kaggia and other leftists pushing for genuine land reform and wealth redistribution. He maintained connections with progressive movements across Africa and Asia. His journalism exposed corruption and challenged the consolidating power of the Kenyatta government. Pinto understood that independence without economic justice was a hollow victory. The British had left, but their economic system remained intact, now operated by African compradors serving international capital rather than their own people.

February 24, 1965. Pinto was shot outside his home in Nairobi by gunmen who were never seriously pursued. He was 38 years old. His murder came at a crucial moment—just as opposition to Kenyatta’s authoritarian drift was organizing. Killing Pinto removed a key intellectual force behind the emerging left. The assassination was amateur in execution but professional in effect. A scapegoat was eventually convicted and hanged, but questions about who ordered the killing were never answered. Pinto’s widow and children fled Kenya, fearing for their lives. His publications were shut down. His name was systematically erased from official histories. The crime wasn’t just his murder—it was the deliberate amnesia that followed, the decision that his contribution to Kenya’s liberation was too dangerous to remember.

The Statues That Lie: Manufacturing Heroes in Bronze

The Kenyatta Cult

Statues, portraits in every office, streets renamed, face on currency—the state manufactured a personality cult around a man whose actual contribution to armed struggle was imprisonment.

Selective Memory

Monuments commemorate acceptable heroes while radical figures like Pinto and Kimathi remain unmarked, unmemorialized, deliberately forgotten by official history.

Public Space as Propaganda

Every statue, every renamed street, every official memorial site tells a story about power—who holds it, how they got it, and which version of history serves their interests.

Walk through Nairobi and you’ll encounter monuments to Kenya’s liberation struggle at nearly every turn. The Kenyatta International Conference Centre dominates the skyline. Kenyatta Avenue runs through the city center. Kenyatta University educates thousands. His statue stands at KICC, stern and commanding. His face appeared on currency for decades. Every public school displayed his portrait. The message is clear—Kenyatta liberated Kenya. This historical narrative serves a political function. By elevating Kenyatta to singular heroic status, the state legitimizes his betrayals, obscures the collective nature of the struggle, and establishes a founding myth that justifies elite rule.

Kimathi’s statue wasn’t erected in central Nairobi until 2007—over fifty years after his execution. The delay was not bureaucratic oversight. It was political calculation. Kimathi represented armed resistance, radical redistribution, and a refusal to compromise. These are dangerous memories for a government built on elite accumulation and political repression. When the statue was finally built, it faced immediate controversy. Some claimed the statue didn’t accurately represent Kimathi. Others questioned its location. The debates missed the larger point—that half a century of deliberate erasure couldn’t be undone by a single monument. Kimathi’s absence from public memory during Kenya’s formative decades had already accomplished its purpose.

Public monuments are never neutral. They encode power relations, legitimize certain narratives, and exclude others. Kenya’s landscape of memorialization reveals what the state wants citizens to remember and forget. Heroes are those who can be safely monumentalized without raising uncomfortable questions about the present. Radicals who demanded economic justice, who criticized corruption, who refused to accept that independence had to mean merely replacing white rulers with black ones—these figures remain unmarked, unmemorialized, consigned to academic papers and fading memories. The bronze and marble we’ve erected don’t preserve our history. They distort it, offering comforting lies instead of difficult truths.

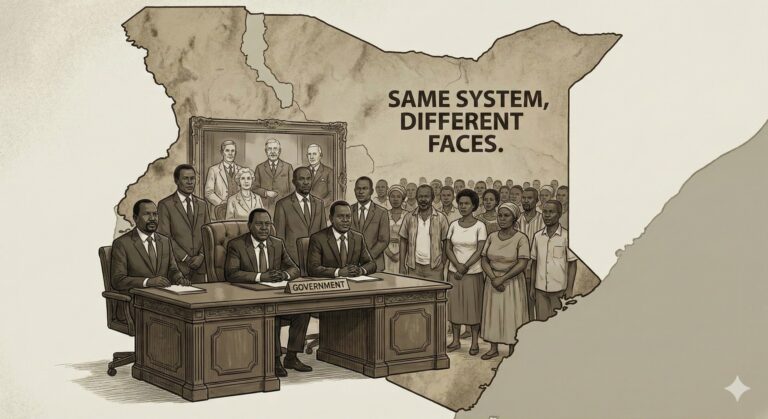

What We Lost: The Dream That Died

The Kenya that Kimathi, Kaggia, JM, and Pinto envisioned never materialized. They fought for land redistribution—we got land concentration. They died for economic justice—we got widening inequality. They demanded accountable government—we got ethnic patronage and corruption. They dreamed of a nation where colonial hierarchies would be dismantled—we got the same hierarchies with African faces at the top. The betrayal wasn’t just personal, though Kenyatta’s treatment of his former comrades was deeply personal. The betrayal was structural, systematic, and ongoing. Every land-grabbing scandal, every rigged election, every murdered dissident, every billion shillings looted from public coffers represents another nail in the coffin of the liberation dream.

Sixty years after independence, Kenya remains profoundly unequal. The children of those who fought in the forests often live in slums, unemployed and landless. The children of those who collaborated with colonialism, or who positioned themselves cleverly during the transition, inherited property, businesses, and political power. This wasn’t inevitable. Other choices were possible. Land could have been genuinely redistributed. The economy could have been restructured to serve the masses rather than elites. Political power could have been dispersed rather than concentrated. These paths were advocated, loudly and clearly, by the men we’ve discussed. They were rejected because accepting them would have required sacrifice from those who had positioned themselves to benefit from independence.

The cost of these choices compounds annually. Youth unemployment fuels desperation. Corruption has become systematic rather than episodic. Ethnic tensions explode periodically into violence because patronage politics requires dividing people along tribal lines to maintain power. Every election cycle, politicians invoke tribal loyalty to mobilize votes while looting the state. This wasn’t what the forest fighters died for. This wasn’t what JM demanded before assassins silenced him. This wasn’t what Pinto published before bullets stopped his press. They wanted a different Kenya. We got this one instead. The tragedy isn’t just that their dreams died—it’s that we’ve stopped mourning them, stopped imagining alternatives, stopped believing anything better is possible.

Truth and Reconciliation: What We Owe the Dead

Acknowledge the Lies

Official history has distorted Kenya’s liberation struggle. Schools teach sanitized narratives that obscure who actually fought and what they fought for. Truth requires admitting these distortions.

Honor Real Heroes

Kimathi, Kaggia, JM, Pinto, and countless unnamed fighters deserve more than occasional mentions. Their sacrifices and visions must become central to how Kenya understands itself.

Investigate Murders

JM’s assassination, Pinto’s shooting, and dozens of other political killings remain unsolved. Justice requires reopening these cases, naming perpetrators, acknowledging state complicity.

Redistribute Resources

Honoring the liberation struggle means implementing the economic justice they demanded. Land reform, progressive taxation, and wealth redistribution aren’t radical—they’re overdue.

Kenya has never had a genuine truth and reconciliation process. We’ve had government-appointed commissions that produced reports nobody implemented. We’ve had ritual apologies without structural change. We’ve had symbolic gestures that preserve power relations. Real reconciliation would require powerful people to acknowledge uncomfortable truths about how they acquired their wealth and status. It would require returning stolen land. It would require prosecuting killers who have enjoyed impunity for decades. It would require dismantling the patronage networks that control politics. None of this has happened because those who benefit from the current system control the state machinery that would need to implement reforms.

Truth-telling is dangerous in Kenya. Ask the journalists who’ve been killed for investigating corruption. Ask the activists who’ve been arrested for organizing protests. Ask the historians whose critical research receives no government support. The state protects its founding myths because those myths legitimize current arrangements. Challenging official history means challenging present power. This is why Kimathi remained unmemorialized for half a century. This is why textbooks still center Kenyatta while marginalizing Kaggia. This is why JM’s killers were never seriously pursued. Truth threatens order, and order serves the powerful.

What we owe the dead is honesty. We owe them the admission that we failed to build the Kenya they envisioned. We owe them the acknowledgment that their sacrifices were betrayed by those who claimed their legacy. We owe them a commitment to revive the struggles they died for—struggles for economic justice, political accountability, and genuine equality. This doesn’t mean violence or revolutionary upheaval. It means organizing, demanding, and refusing to accept the lie that independence has been achieved when most Kenyans remain unfree in every material sense. The dead can’t fight anymore. We can. That’s what we owe them.

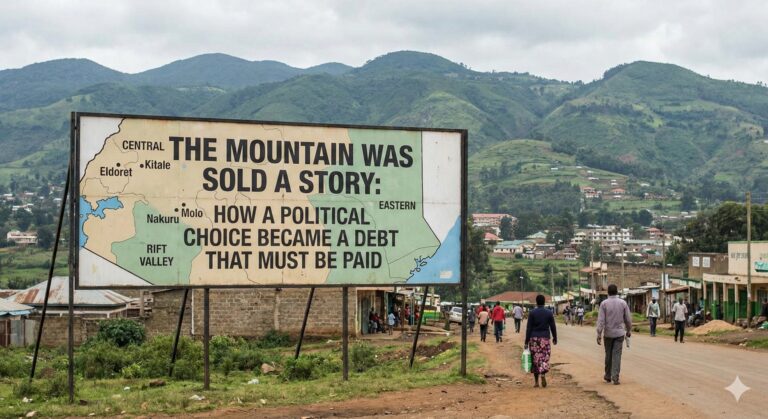

The Story We Tell Ourselves: Choosing Truth

Every nation builds myths about its origins. These myths serve social purposes—creating unity, legitimizing authority, providing shared identity. But myths can become prisons. When the stories we tell about our past are fundamentally dishonest, they corrupt our present and constrain our future. Kenya’s founding mythology—the peaceful transition to independence led by wise statesmen—is such a prison. It prevents us from asking why independence didn’t deliver economic liberation. It stops us from questioning why the same families control resources sixty years later. It makes systemic corruption seem like unfortunate lapses rather than foundational features. Breaking free requires choosing truth over comforting lies.

Choosing truth means teaching children that Kenya’s independence was won primarily through armed struggle, not negotiation. It means acknowledging that the British left only when the costs of staying became unbearable. It means recognizing that those who fought hardest often benefited least. It means admitting that Kenyatta betrayed his comrades and the masses who had suffered under colonialism. It means honoring Kimathi, Kaggia, JM, and Pinto not as footnotes but as central figures whose visions remain unfulfilled. It means understanding that the struggle for liberation didn’t end in 1963—it continues every time someone demands accountability, challenges inequality, or refuses to accept ethnic patronage as inevitable.

The young Kenyans filling streets demanding change understand something their elders forgot. The fight isn’t finished. The dream didn’t die with Kimathi in Kamiti Prison or JM in the Ngong Hills. It lives in every protest against corruption, every demand for justice, every refusal to accept that this is the best Kenya can be. History isn’t fixed. The stories we tell about our past shape our future. Kenya can continue worshipping false heroes and maintaining comfortable lies. Or we can honor the men and women who actually fought for liberation by completing their unfinished work. The choice belongs to us. The dead have done their part. Now it’s our turn.

Educate

Learn the real history, share it, teach it, refuse sanitized versions that serve power

Demand

Accountability for past murders, justice for victims, prosecution of those who’ve enjoyed impunity

Organize

Build movements for economic justice, land reform, genuine democracy beyond ethnic patronage

Remember

Honor true heroes not by statues alone but by continuing struggles they died for